The Life & Career of Leonard Rossiter

A Biography

|

|

~ |

|

~ |

|

The Life & Career of Leonard Rossiter

A Biography

On

October

21st 1926, in the bustling port of Liverpool, North West England, a

second

son was born, at home, to John and Elizabeth Rossiter, and a baby

brother

for John junior. Leonard was raised in the family home above his

father's

barber shop in Cretan Road, Wavertree, a suburb of the city of

Liverpool.

After primary school in Granby St., Toxteth, he attended the city's

Collegiate

Grammar School from 1939 to 1945. He excelled at languages and sport,

both

of which would come in useful in later life. A cheerful, modest,

punctual

and scholarly pupil, Leonard was made vice captain of the school, and

captains

of both the football and cricket teams, where he was " a slow, left-arm

bowler - in true Lancashire style". In one match the school football

team

beat their opponents 11-0, and it was Leonard who scored all eleven

goals.

He was also a member of the school's drama society. Naturally shy,

Leonard

remembers his adolescence with embarrassment: "I remember all those

dances

at The Rialto, Liverpool, where I spent every Saturday night between

10.30

and 11. Well, I hated it. The whole evening was geared to that last

half-hour.

The last waltz, or whatever. Mostly the whatever." When he started to

mix

with people from different social classes, he would always hold back if

he wasn't sure how to conduct himself: "I remember getting very hot

under

the collar at dinner tables... I was always afraid of being laughed at."

World

War Two began shortly before Leonard's thirteenth birthday, but he

still

had hopes of studying a French and German degree course at university.

His father was now a volunteer ambulance man, helping to ferry the

wounded

to Liverpool's hospitals. Tragically, in 1942, John Rossiter was killed

performing this duty during an air raid. Leonard now had to re-think

his

future, especially with regards to supporting his mother. Before then,

however, he would reach conscription age, and have to 'do his bit' for

the war effort. He joined the Education Corps. based at Bielefelt in

Germany.

By now the Germans had surrendered but the Japanese were still

fighting.

To give him an authority as instructor, he was instantly made a

sergeant.

Leonard would spend his time there teaching soldiers their ABC, and

often

had to write their letters home. Many men were less than keen to learn:

"Lots of chaps resented it", Leonard recalls. "Most of them were

totally

hardened to the idea of never needing to read or write and didn't see

why

they should start."

Sergeant

Rossiter was demobbed in 1948 and, despite being offered his dream

place

at Liverpool University to study languages, turned it down to become

the

breadwinner for the Rossiter household. Through a school friend he got

himself a job with Commercial Union, one of the country's largest

insurance

companies. He was a clerk in the claims and accidents department,

earning

£210 per year. Although frustrated at being tied to a desk all

day,

he stayed with the firm for six and a half years. Many years later he

would

joke about his time at the CU: "It really is amazing how many

entertainers

started life in insurance", he quipped, "and most of them will still

try

to sell you some, given half a chance." One of his colleagues in the

same

office was the late actor Michael Williams, husband of Dame Judi Dench.

Michael remembers: "Len was the most competitive man ever. We used to

play

football for the office team. Once, he passed me the ball by an open

goal.

I missed it. Len wouldn't speak to me for a week. And we sat at

opposite

desks!"

Leonard

had a girlfriend during this time who was an amateur actress with a

local

drama group. Rehearsals were over-running one night when he went to

pick

her up, and Leonard got to see their performances. He was not very

impressed

by any of them, including his girlfriend's! She challenged him to do

better,

and so he did. His daughter Camilla remembers: "He always told the

story

that his girlfriend was an amateur actress and he went along and saw

her

once and said 'I can do better than that'". Leonard himself recalls:

"Really,

it was only to see more of the girl. Then I got more interested in the

stage than I did in the girl". When he'd made the decision to become an

actor, he decided to move away from Liverpool, but "he always had a

fondness

for [the city]. He was always proud of where he came from." He became a

member of The Adastra Players, and later also joined The Centre Players

drama group, based at the Wavertree Community Centre in Penny Lane

(long

before The Beatles made it a far more famous street). With an annual

subscription

of two shillings - ten pence - Leonard was in his element, despite a

stage

measuring just 16 feet by 10 feet. Before long, Leonard was acting with

five drama societies, and his acting talents were so in demand that he

was often rehearsing for two roles while acting in another. His first

public

performance was with The Adastras in a Terence Rattigan play called

Flare

Path, in which he played the role of Flight Lieutenant Graham.

Criticism

was positive, although one critic faulted him on his rapid rate of

delivery,

something which Leonard, wisely, never rectified.

Between 1949 and 1954 Leonard acted in nearly forty plays, and soon

found

his day job getting in the way. Although now earning £10 a week

at

the CU, and barely £6 on stage, it was acting that Leonard

desperately

wanted to concentrate on - so much so that he started to have elocution

lessons to lose his Liverpudlian accent. He took the decision to leave

the insurance business and become a full-time actor. As Leonard himself

said years later, when discussing his apparently brave decision to

quit:

"It would have been far more courageous to have stayed in the insurance

business, knowing I'd be bored out of my mind for the rest of my life."

Between 1949 and 1954 Leonard acted in nearly forty plays, and soon

found

his day job getting in the way. Although now earning £10 a week

at

the CU, and barely £6 on stage, it was acting that Leonard

desperately

wanted to concentrate on - so much so that he started to have elocution

lessons to lose his Liverpudlian accent. He took the decision to leave

the insurance business and become a full-time actor. As Leonard himself

said years later, when discussing his apparently brave decision to

quit:

"It would have been far more courageous to have stayed in the insurance

business, knowing I'd be bored out of my mind for the rest of my life."

And so

it was, in August of 1954, that Leonard Rossiter, now a top amateur

actor

in the North West of England, auditioned for Preston Repertory Company,

based in the town's now-defunct Royal Hippodrome: "I think it's

C&A's

now", Leonard said in an interview. The production manager, Reginald

Salberg,

was casting a part in a production of Joseph Colton's The

Gay Dog, and Leonard tried for the part. He read the part badly,

however,

and the play's director Alan Foss had dismissed him when Salberg,

sensing

a talent, asked him to read the part again. This Leonard did, equally

badly

- but differently, and Leonard got the part. It was September 6th,

1954,

then, that Leonard Rossiter first performed as a professional actor, in

the role of Bert Gay, for £2.50 a fortnight. Co-star Frederick

Jaeger

recalls: "Len was dedicated and a perfectionist even in those days. He

was so intense about his work which meant he wasn't the most relaxed of

people... He expected everyone to work as hard as he did". So

pleased

were Reggie Salberg and Alan Foss with Leonard's performances that he

was

engaged as ASM - assistant stage manager. In all, he performed fourteen

plays at Preston Rep., until the theatre closed in the spring of 1955.

Wolverhampton

Repertory Company at The Grand Theatre was Leonard's next stop where,

from

April 1955 until the end of 1958, Leonard honed his natural talent and

skill with over fifty roles in productions of plays by such authors as

Agatha Christie, Graham Greene and Moliere.

Many productions were directed by John Barron, who became a lifelong

friend,

introduced Leonard to the world of fine wines, and later formed one of

television's most fondly-remembered worker-boss duos: Reggie

Perrin and C.J. His passion for football still as active as ever,

Leonard

used to see half of Wolverhampton Wanderers' matches at the Molyneux

(then

skippered by the late, great Billy Wright), before racing back to The

Grand

to prepare for his role (an Evertonian by tradition, Tommy Lawton was

Leonard's

footballing hero). It was at this point in his life - during rep. -

that

Leonard learned one of his most amazing skills: the ability to learn

vast

amounts of dialogue. Looking back on this time Leonard recalls: "There

was no time to discuss the finer points of interpretation. You studied

your part, you did it and then you studied the next part. I developed a

frightening capacity for learning lines. The plays became like

elastoplast,

which you just stuck on and then tore off." During this time,

television

became Leonard's second media format in 1956 when he landed a bit part

in a BBC play entitled Story

Conference, broadcast in March of that year.

Even so early in his

career,

those who worked with Leonard found him to be an absolute

perfectionist,

and totally committed to everything he did. John Graham, Leonard's

co-star

in She

Would And She Would Not at Salisbury R ep. (based at

The Playhouse,

where Leonard spent the first half of 1959) remembers him as: "a quiet,

thinking man who observed and absorbed. He was a perfectionist and

expected

not only 100% dedication to the job in hand from himself but also from

others." A comment that echoes down the years, from theatre to film to

television. John Bowen recalls Leonard reminiscing about how great his

training was in rep.: "During his first two years, he said, everything

which could happen, did happen. Doors stuck, lights wouldn't come on or

go off, scenery fell down, rain dripped through holes in the roof,

fellow

actors dried or missed their entrances - and so did he - the curtain

fell

when it shouldn't, or refused to rise, the ASM tried to prompt from the

text of a different play. By the end of two years nothing could

surprise

him - he already knew that he could cope with it, and had the

confidence

of that knowledge". It was while at Salisbury Rep. that Leonard met a

young

actress called Josephine Tewson. They acted together in The

Food Of Love, A

Cuckoo In The Nest and Book

Of The Month, amongst others. Gradually, they became good friends,

and then lovers, and were soon married. (Josephine has since become a

familiar

face on British TV screens, for her portrayal as Hywel Bennett's

landlady

in Shelley, as Ronnie Barker's wife in Clarence, and more recently as

Liz,

Hyacinth Bucket's (pronounced 'Bouquet'!) long-suffering neighbour in

Keeping

Up Appearances).

ep. (based at

The Playhouse,

where Leonard spent the first half of 1959) remembers him as: "a quiet,

thinking man who observed and absorbed. He was a perfectionist and

expected

not only 100% dedication to the job in hand from himself but also from

others." A comment that echoes down the years, from theatre to film to

television. John Bowen recalls Leonard reminiscing about how great his

training was in rep.: "During his first two years, he said, everything

which could happen, did happen. Doors stuck, lights wouldn't come on or

go off, scenery fell down, rain dripped through holes in the roof,

fellow

actors dried or missed their entrances - and so did he - the curtain

fell

when it shouldn't, or refused to rise, the ASM tried to prompt from the

text of a different play. By the end of two years nothing could

surprise

him - he already knew that he could cope with it, and had the

confidence

of that knowledge". It was while at Salisbury Rep. that Leonard met a

young

actress called Josephine Tewson. They acted together in The

Food Of Love, A

Cuckoo In The Nest and Book

Of The Month, amongst others. Gradually, they became good friends,

and then lovers, and were soon married. (Josephine has since become a

familiar

face on British TV screens, for her portrayal as Hywel Bennett's

landlady

in Shelley, as Ronnie Barker's wife in Clarence, and more recently as

Liz,

Hyacinth Bucket's (pronounced 'Bouquet'!) long-suffering neighbour in

Keeping

Up Appearances).

Leonard

was based at the Theatre Royal, Bristol until the summer of 1961, with

the Old Vic Company, by which time he had had his first taste of

performing

in major Shakespearean productions, including The

Comedy Of Errors, Richard

II, The

Tempest and Romeo

and Juliet, which he performed at the famous Baalbek festival.

Although

still only playing minor roles, it was still a firm foundation for his

acting skills - "Our repertory system is the best theatrical training

in

the world. When my London 'break' came eventually I felt ready for it",

Leonard said. That 'break' came in June 1957, performing in front of

his

first London audience, with Josephine, when he appeared in Free

As Air at The Savoy Theatre. And another television appearance, in

1959 in a play called The

Constable's Move, ensured his talents would never be exclusively

theatre-based.

By now, Leonard was the leading man at The Old Vic, and his name was

being

uttered up and down the country, as a force to be reckoned with. The

commitment,

energy and drive he gave to each role was now more concentrated than

ever,

and he was often described as being like 'a coiled spring'. More

television

followed, and his first feature film. In A

Kind Of Loving, Leonard had just one scene, as a draughtsman in an

office with Alan Bates and James Bolam. Leonard recalls the film: "It

was

about the time that the so-called 'kitchen sink' era was well

established.

I felt much more at home in those types of plays and films. I would

never

have made it at all as an actor if there had not been that sort of

revolution

in English theatre..." Personally, however, Leonard's marriage to

Josephine

Tewson was in trouble, and they had separated. "We greatly admired each

other, in our  work",

she recalls, "But we mistook that for love".

work",

she recalls, "But we mistook that for love".

1962

was to be a better year for Leonard Rossiter. At the Belgrade Theatre,

Coventry, Leonard starred in a play about a greedy, manipulative

insurance

agent by the name of Fred Midway. The play was called Semi-Detached,

and opened on June 9th. Leonard made the part his own, and critics

raved

about his role. One of his co-stars was the actress Gillian Raine, and

by the time the play was chosen to be part of a 'British season' on

Broadway,

New York, in 1963, their working relationship had developed into a

personal

one, and the couple were in love. Gillian remembers his role as Fred

with

great feeling: "I think one sensed when one first saw him that he was

exceptional

and different, in that he had a sort of manic, farcical talent." Sadly,

the British humour of Semi-Detached was lost on American audiences, and

the play soon closed. Leonard said: "When I worked over there I came to

a firm conclusion - we are separated by a mutual language." Just to add

insult to Leonard's injury, when the play transferred to London, it was

Laurence Olivier who was cast as Fred Midway. It would be another six

years

before Leonard would get the West

End breakthrough he deserved. In the meantime, he was becoming a

familiar

face in people's living rooms when he landed the regular role as

Detective

Inspector Bamber in the popular police drama series Z

Cars. More plays kept Leonard busy during 1963, and even an

appearance

as a fancy-dress Robin Hood in an episode of The

Avengers. On the big screen, he appeared alongside Richard Harris

in

This

Sporting Life, and played a very memorable Mr. Shadrack, the

undertaker

boss of Tom Courtenay's Billy Fisher in Billy

Liar.

By 1964, Leonard was, for the first time in his life, having to

sacrifice

theatre roles for those in other media. Theatre was always Leonard's

favourite

medium and he would always return to it whenever the opportunity

presented

itself: "You get a much greater sense of doing the job more

successfully

working in the theatre", he once said, and later "...[T]heatre is my

favourite

[medium] I suppose - audiences are very important to me." But of

course,

his biggest audiences were on nationwide television: "Many people

remember

Leonard solely for his TV work", says Gillian, "but he did more stage

work

than anything else. He got slightly annoyed whenever he was referred to

as a 'small-screen' actor". But the roles that made Leonard a household

name were still a decade or more away. In 1964, while still busy with Z

Cars, he could be seen in a supporting role in the Steptoe

And Son episode 'The Lead Man Cometh', in which he played the type

of character he was by now often getting cast as - namely, shady

criminal

types in raincoats. He also recorded his only war film at this time, King

Rat - filmed in Hollywood - in which he played a British Colonel in

a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp, with fellow prisoners including George

Segal, James Fox and John Mills. His comedic talents were now being

recognised,

and in 1965 he became a regular on the late-night satirical review show

BBC-3,

and in 1968 another satire show At

The Eleventh Hour. Plays For Today and similar dramas continued to

occupy Leonard throughout the mid-sixties (including a BBC version of

one

of his favourite theatre productions

Semi-Detached),

and no less than five films were released in 1966 in which he played at

least a minor role, opposite stars such as Michael

Caine, Edith

Evans and Joan

Fontaine.

By 1964, Leonard was, for the first time in his life, having to

sacrifice

theatre roles for those in other media. Theatre was always Leonard's

favourite

medium and he would always return to it whenever the opportunity

presented

itself: "You get a much greater sense of doing the job more

successfully

working in the theatre", he once said, and later "...[T]heatre is my

favourite

[medium] I suppose - audiences are very important to me." But of

course,

his biggest audiences were on nationwide television: "Many people

remember

Leonard solely for his TV work", says Gillian, "but he did more stage

work

than anything else. He got slightly annoyed whenever he was referred to

as a 'small-screen' actor". But the roles that made Leonard a household

name were still a decade or more away. In 1964, while still busy with Z

Cars, he could be seen in a supporting role in the Steptoe

And Son episode 'The Lead Man Cometh', in which he played the type

of character he was by now often getting cast as - namely, shady

criminal

types in raincoats. He also recorded his only war film at this time, King

Rat - filmed in Hollywood - in which he played a British Colonel in

a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp, with fellow prisoners including George

Segal, James Fox and John Mills. His comedic talents were now being

recognised,

and in 1965 he became a regular on the late-night satirical review show

BBC-3,

and in 1968 another satire show At

The Eleventh Hour. Plays For Today and similar dramas continued to

occupy Leonard throughout the mid-sixties (including a BBC version of

one

of his favourite theatre productions

Semi-Detached),

and no less than five films were released in 1966 in which he played at

least a minor role, opposite stars such as Michael

Caine, Edith

Evans and Joan

Fontaine.

Although

always priding himself on getting just right the characterisations of

every

role he played, Leonard did surprisingly little research of the

background

events of his performances, especially historical detail. He expected

the

play or drama itself to set the scene and explain things for him and

his

audience: "I was dreadful at history", he wrote in his 1981 book The

Lowest Form Of Wit, adding: "Partly because of my lack of interest

in history and partly because of an in-built conviction that too much

research

leads to cranky performances, I never dug too deeply into the private

lives

of any historical characters I've attempted - Voltaire,

Hitler,

Giordano

Bruno or Richard

III. If the author doesn't achieve his aim between pages 1 and 80

no

amount of research by an actor will do it". But one of the greatest

aspects

of Leonard's art that most people who worked with him remember, was his

fantastic ability to adapt to any situation. As John Wells commented:

"Serious

actors can't do comedy, but comics as good as Len can do anything - he

showed the whole range. He was a very, very, very good actor. I think,

if you can do comedy as well as Len did, you can do anything."

Leonard's

capability as an all-round, versatile actor found him being cast in

much

more substantial, and often controvertial roles. For example, in the

BBC

drama Drums

Along The Avon, Leonard played Mr. Marcus, a crackpot who, in an ef fort

to cement good relationships with the local ethnic communities, blacks

himself up as a Muslim and a Sikh, complete with towel for turban. It

was

these kind of powerful, socially-aware dramas that were being made at

this

time, and Leonard was one of the few really powerful character actors

who

could pull off a role such as this. Indeed, his theatre portrayal of

Adolf

Hitler as a gangster-type racketeer-turned-dictator in The

Resistible Rise Of Arturo Ui was seen by many as one of the great

virtuoso

performances of our time. The play, by Bertolt Brecht, premiered in

Glasgow

in September 1967, but it was its West End debut in July 1969 at the

Saville

Theatre that made people really sit up and take notice of the

devastating

brilliance of the man in the lead role. Until that time, Brecht's plays

were never performed in London's theatre land - all the more amazing

then

that this show, with Leonard at its helm, should become such a

phenomenal

success. This became, and was to remain, Leonard's favourite

contribution

to British theatre, and few have forgotten its impact. Leonard himself

found the role had all the elements that he could play really well, and

it was a personal triumph for him. He won three awards for his

outstanding

performance as Ui, but his modesty came through, even then:

fort

to cement good relationships with the local ethnic communities, blacks

himself up as a Muslim and a Sikh, complete with towel for turban. It

was

these kind of powerful, socially-aware dramas that were being made at

this

time, and Leonard was one of the few really powerful character actors

who

could pull off a role such as this. Indeed, his theatre portrayal of

Adolf

Hitler as a gangster-type racketeer-turned-dictator in The

Resistible Rise Of Arturo Ui was seen by many as one of the great

virtuoso

performances of our time. The play, by Bertolt Brecht, premiered in

Glasgow

in September 1967, but it was its West End debut in July 1969 at the

Saville

Theatre that made people really sit up and take notice of the

devastating

brilliance of the man in the lead role. Until that time, Brecht's plays

were never performed in London's theatre land - all the more amazing

then

that this show, with Leonard at its helm, should become such a

phenomenal

success. This became, and was to remain, Leonard's favourite

contribution

to British theatre, and few have forgotten its impact. Leonard himself

found the role had all the elements that he could play really well, and

it was a personal triumph for him. He won three awards for his

outstanding

performance as Ui, but his modesty came through, even then:  "Prizegiving

in acting is very pleasant and it's nice to win, but it's all a bit

ridiculous",

he said in a 1978 interview. "How can you compare two actors'

performances

in quite different plays? I'm not saying prizes shouldn't exist,

because

I've had a few myself, but they're not to be taken seriously".

Meanwhile,

between the premiere of Ui in 1967 and its storming of the box office

in

1969, Leonard was as busy as ever. He played the undertaker Mr.

Sowerberry

in the film version of Lionel Bart's Oliver!

("...I don't like Dickens being 'prettied up' ", said Leonard, "David

Lean's

'Oliver Twist' is more to my liking, but it was a pleasant

experience."),

and was back playing a criminal - this time an assassin for hire - in

Clement

and La Frenais' Otley.

Science fiction featured prominently for Leonard in 1968, first in the

TV play The

Year Of The Sex Olympics, and then in a cameo role on the

big-screen

in Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece 2001:

A Space Odyssey.

"Prizegiving

in acting is very pleasant and it's nice to win, but it's all a bit

ridiculous",

he said in a 1978 interview. "How can you compare two actors'

performances

in quite different plays? I'm not saying prizes shouldn't exist,

because

I've had a few myself, but they're not to be taken seriously".

Meanwhile,

between the premiere of Ui in 1967 and its storming of the box office

in

1969, Leonard was as busy as ever. He played the undertaker Mr.

Sowerberry

in the film version of Lionel Bart's Oliver!

("...I don't like Dickens being 'prettied up' ", said Leonard, "David

Lean's

'Oliver Twist' is more to my liking, but it was a pleasant

experience."),

and was back playing a criminal - this time an assassin for hire - in

Clement

and La Frenais' Otley.

Science fiction featured prominently for Leonard in 1968, first in the

TV play The

Year Of The Sex Olympics, and then in a cameo role on the

big-screen

in Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece 2001:

A Space Odyssey.

More

acclaimed theatre roles followed in the early 1970s, notably as Richard

III and Davies the tramp in Harold Pinter's The

Caretaker. He was determined that "acting shouldn't become a nine

to

five job", and was keen to avoid a 'long run' of a play: "They're a

bore",

he said. In 1972, Leonard returned to the sitcom Steptoe

And Son to play an escaped convict who took the two scrap dealers

hostage.

One person who saw that episode, and was struck by Leonard's powerful

performance,

was playwright Eric Chappell: "To come onto that show and almost

overpower

Wilfrid Brambell and Harry H. Corbett shows how strong he was." Eric

had

found the actor he needed for his play The

Banana Box.

On

a personal level, Leonard and Gillian Raine were married, and in 1972

Gillian

gave birth to a daughter, Camilla. They lived in London, off the Fulham

Road, close to Chelsea football stadium. Their house, which they shared

with their two Abyssinian cats Honey and Vicky, backed onto Brompton

cemetery,

a 38-acre sprawling Victorian graveyard, and final resting place of

such

dignitaries as the suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, singer Richard

Tauber

and Brandon Thomas, author of Charley's Aunt. He once quipped on the

cemetary's

residents: "They're good neighbours - very little noise and no

late-night

parties!" Leonard would often unwind by strolling through the cemetery,

and reading the epitaphs. Leonard's love of fine wines, generated by

his

former director, and later Reginald

Perrin co-star John Barron way back in the 1950s, resulted in him

adding

another floor to his house: "Only a man who could so closely match

Reggie

would put his cellar in the attic!", remembers John. Leonard the

connoisseur

amassed several hundred bottles of vintage wines and, not surprisingly,

spent quite some time on his newly-added floor: "It's got glass doors along

the front" he beamed, "where I sit sunning myself and learning my

lines.

Just a hand-stretch away is the attic...!" He was quick to admit,

though,

that he and Gillian were not 'social animals': "We prefer small dinner

parties to large gatherings and seldom go out except to the theatre

(which

we do regularly). Otherwise, I read a lot and drink wine a lot!".

Leonard

would play squash once,  sometimes twice a day, despite only taking up the

sport at the age of 36. "I suppose fitness is important, living at my

pace",

he once said, adding "I like to win. I think fooling around in sport is

very tedious. It needs a fairly good player to outclass me now". He was

often to be seen as a member of charity cricket, tennis, squash or

football

teams, and usually a prominent member of those teams, even in his

fifties.

On his passion for cricket Leonard says: "I almost took up cricket as a

career before the War. I was a Lancashire Colt...I enjoy these sorts of

fundraising activities provided we can field a good side in both games

- it's only fair to the spectators. Just to pay good money to see a few

celebrities knocking a ball about is not very worthwhile, is it?" His

favourite

charity was the Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund For Children, for which he

helped raise thousands of pounds over the years, in many sporting

tournaments.

Away from

sometimes twice a day, despite only taking up the

sport at the age of 36. "I suppose fitness is important, living at my

pace",

he once said, adding "I like to win. I think fooling around in sport is

very tedious. It needs a fairly good player to outclass me now". He was

often to be seen as a member of charity cricket, tennis, squash or

football

teams, and usually a prominent member of those teams, even in his

fifties.

On his passion for cricket Leonard says: "I almost took up cricket as a

career before the War. I was a Lancashire Colt...I enjoy these sorts of

fundraising activities provided we can field a good side in both games

- it's only fair to the spectators. Just to pay good money to see a few

celebrities knocking a ball about is not very worthwhile, is it?" His

favourite

charity was the Malcolm Sargent Cancer Fund For Children, for which he

helped raise thousands of pounds over the years, in many sporting

tournaments.

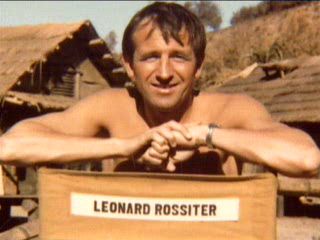

Away from  the

sports grounds, Leonard was also in demand for many other charity

events,

which he gladly participated in, including being a male model, as

exemplified

by the knitting pattern (pictured, right), proceeds from the sale of

which

went to Oxfam's Move Against Poverty campaign.

the

sports grounds, Leonard was also in demand for many other charity

events,

which he gladly participated in, including being a male model, as

exemplified

by the knitting pattern (pictured, right), proceeds from the sale of

which

went to Oxfam's Move Against Poverty campaign.

In

the

spring of 1973 Leonard, who was by now one of the country's most

in-demand

actors, starred in Eric Chappell's play

The

Banana Box, about a miserly landlord called Rooksby who,

unashamedly

bigoted and racist, finds himself landlord to a black man, and an

African

prince to boot. The play had success written all over it and Yorkshire

Television were keen to turn it into a series. And so, as 1974 came to

a close, a new situation comedy hit viewers' screens. Entitled Rising

Damp, it followed the same storyline as the play and was written by

the play's author Eric Chappell. The part of Rigsby did for Leonard on

television what Arturo Ui did for him on stage. Leonard was now a

massive

star, and any other performance (he was still recording plays and

occasional

films) were watched religiously. This was Leonard's first series,

something

he'd always tried to avoid: "I never wanted to do a series", he said in

1978, "Normally you make up your mind on the basis of the script for

the

first episode. By the time you get to the third, the standard has gone

down, and by the time you get to the fifth, you wish you'd never done

it".

It was only his faith in Eric Chappell and the strength of the story

that

Leonard decided he would do the first series. Three more series of

Rising

Damp were made, securing the programme as ITV's biggest ever hit, and

one

of the greatest sitcoms of all time. "People ask me regularly if I have

based the character on a particular landlord. Happily, I only knew

landladies

- and very nice they were, too !" Earlier in 1974, Leonard was offered

the role of Sergeant Major Williams in a new sitcom for the BBC called

It Ain't Half Hot, Mum, written by Dad's Army and Hi-De-Hi! creator

Jimmy

Perry. However, when the two men met, Leonard psychoanalysed the

character

in his usual meticulous manner, and gave Jimmy advice on changes to the

script, much to the annoyance of Jimmy Perry. Some writers took this

analysis

by Leonard as a sign of genius, others took it as 'interfering'. Jimmy

Perry was of the latter persuasion, and the role went instead to Welsh

actor Windsor Davies.

After

the runaway success of Rising Damp on ITV, the BBC were eager to grab

Leonard

for a show of their own. They had already accepted the novel The Death

Of Reginald Perrin by David Nobbs as potential for a series, and Jimmy

Gilbert, then head of comedy at the BBC, saw his opportunity at last.

Leonard

played the frustrated, middle-aged sales executive the way only Leonard

could - powerfully and brilliantly, and The

Fall And Rise Of Reginald Perrin quickly followed Rising Damp into

the realms of 'classic comedy'. But as with Rising Damp, Leonard was

wary

of committing himself to a series: "I only did it because it had been a

novel first, and the author had adapted it for television". Two more

series

followed, all three wonderfully written and staggeringly performed. But

amongst all this, Leonard continued  to return to his theatrical roots,

most notably as the eccentric painter Benjamin Haydon in John Wells'

play

The

Immortal Haydon. And still

to return to his theatrical roots,

most notably as the eccentric painter Benjamin Haydon in John Wells'

play

The

Immortal Haydon. And still  the

successes came. Leonard entered the world of commercials in 1977 as a

traffic

warden in an ad for Parker

Pens. But it was his teaming-up with Joan Collins in the classic Cinzano

commercials that will be remembered for ever as masterpieces of

30-second

comedies. Leonard even entered children's television, reading

storybooks

on Jackanory

and becoming the voice of Boot, in the animated version of Maurice

Dodd's

cartoon strip The

Perishers. Voice-overs for commercials

also provided work for Leonard, one of the few things he did purely for

the money: "It doesn't require a great deal of acting brightness or

intelligence.

And the rewards are inordinately high for 'going through the motions'".

He returned to his role of Rigsby for a feature-length version of the Rising

Damp series, and could also be seen as Joseph Pujol, aka Le

Petomane, who's elastic anus had the Moulin Rouge in stitches in

the

late 19th Century. For Leonard, the 1970s was, without doubt, his most

successful - and busiest - decade in his thirty year career.

the

successes came. Leonard entered the world of commercials in 1977 as a

traffic

warden in an ad for Parker

Pens. But it was his teaming-up with Joan Collins in the classic Cinzano

commercials that will be remembered for ever as masterpieces of

30-second

comedies. Leonard even entered children's television, reading

storybooks

on Jackanory

and becoming the voice of Boot, in the animated version of Maurice

Dodd's

cartoon strip The

Perishers. Voice-overs for commercials

also provided work for Leonard, one of the few things he did purely for

the money: "It doesn't require a great deal of acting brightness or

intelligence.

And the rewards are inordinately high for 'going through the motions'".

He returned to his role of Rigsby for a feature-length version of the Rising

Damp series, and could also be seen as Joseph Pujol, aka Le

Petomane, who's elastic anus had the Moulin Rouge in stitches in

the

late 19th Century. For Leonard, the 1970s was, without doubt, his most

successful - and busiest - decade in his thirty year career.

Leonard

is sometimes remembered as having had a reputation for being difficult

to work with: "It's not that I can't tolerate fools," he once said, "I

can, providing that I don't have to put up with them for too

long.

But if you find yourself sitting next to someone who continues to call

you 'Mr. Perrin, sorry I mean Rigsby', and then falls about laughing at

this wonderful turn of phrase, there's nothing much you can do except

shut

him up or leave. I usually leave." However, many people were quick to

defend

his abrasiveness: "He was a tetchy perfectionist, impatient of laziness

and circumstances in which he could not do his best work", recalls

director

Patrick Dromgoole. "But he was also generous, very generous, and

sharply

aware of the strains on those around him". Reginald Perrin co-star

Bruce

Bould sums it up by saying: "Occasionally, before a recording, Len

would

blow up at somebody. Usually there was a very good reason and if

sometimes

there wasn't you could understand that all that nervous energy and

tension

had to go somewhere, and it was a small price to pay for the superb

performances

he gave." Nevertheless, Leonard received an unusual accolade from

members

of the public, as Leonard told an interviewer on ITV's Sunday Sunday

programme

in 1984: "During the '70s, a Women's group, up in the North [of

England],

had voted me "Person You'd Least Like To Be Left Alone In A Room With"

! I wasn't quite sure what to make of that!"

In the

summer of 1979, Leonard Rossiter went into the studios of BBC Radio 4

for

a live radio interview in the slot known as Guest Of The Week. The

interview

was conducted by one of radio's most experienced broadcasters, Sue

MacGregor.

The interview was to become the start of an adulterous affair for

Leonard.

The day after the interview, Leonard rang Sue at the studios and they

went

for a drink, at the end of which Leonard asked for Sue's home phone

number.

So began a clandestine liaison lasting at least two years which saw

Leonard

paying visits once a week to Sue's flat in Primrose Hill, London,

sometimes

hiding behind a handkerchief to preserve anonymity. Sue had never been

married, but Leonard was married to Gillian Raine at this time. Details

of the affair only emerged in Spring 2002 when Sue MacGregor

published

her autobiography

'Woman Of Today'. She wrote to Gillian and Camilla before the book was

published and told her about the affair.

In an interview to publicise her book, she said: "I suppose I regret

the

affair and the unhappiness it caused both me and more importantly his

family.

But there we are, it happened and I have written about it as honestly

as

I could." In another interview for the Daily Mail, she described the

affair

in detail: "I'm not proud of my relationship with Leonard. I don't

regret

it because I loved him, but it was probably very foolish of me to have

got involved. I do think very much about his wife, actually, and his

daughter.

I feel that they must have been horribly shocked when they heard about

it. I don't think they knew anything at all about it." Their discreet

liaisons

were conducted almost entirely at Miss MacGregor's London flat. They

rarely

spent more than two hours in each others' company before he returned to

his family. They never spent a whole night together and he did not

introduce

her to his friends. Sue remembered how the actor, a wine enthusiast,

would

frequently arrive with a bottle of fine vintage. "We'd have a drink and

talk and, yes, if you put it so bluntly, then go to bed. He made it

quite

clear from the beginning that he would never leave his wife," she told

the Daily Mail. Miss MacGregor said: "I was astonished because I was

bedazzled

by him. I'd been very enthusiastic about

his acting and I thought he just wanted to have another chat. It was

rather

naive of me because it was perfectly plain that he wanted more than

that.

He took my home telephone number and started coming to my flat. In the

beginning I was just rather excited by the fact that he was interested

in me, but then I fell in love with him. It was a strange match in many

ways, but we were both quite serious people."

Leonard was

always direct and honest about what he expected from the relationship

and

never gave her the impression of being unhappy in his marriage. On her

part, Sue never suggested that he should leave his wife. "I knew he

never

would and he made that plain. It might sound naive, but I had no

intention

of breaking up his marriage," Sue said. "I'm sure he loved his wife. He

didn't string me along with any line about 'my wife doesn't understand

me'. And he was extremely fond of his daughter, so I don't feel good

about

that at all." The strain of keeping the relationship secret began to

tell

and Sue eventually demanded more. She said: "One day in the flat I just

said: 'I know that I went into this with my eyes open, but I do find

not

being seen with you in public at all very difficult. We have our

relationship

entirely within these four walls. "He said rather coldly: 'Well, you

knew

what you were entering into.' And I agreed with him. So there was

really

nothing more to say and that particular day we parted not very

amicably.

He'd only spoken the truth, but I felt miserable."

Sue

MacGregor

learnt of Leonard's sudden death backstage in the West End in October

1984

from an 8am radio bulletin. "I was having a lie in, which was unlike

me,

and I heard the newsreader say: 'The actor Leonard Rossiter died last

night.'

I felt stunned," she recalled. "I often wonder whether he'd tried to

ring

me the night he died and got no reply." Unable to grieve publicly, she

suffered panic attacks for six months after his death. When Miss

MacGregor

decided to write her book, colleagues asked if she would include

details

of the affair. Persuaded by publishers to include the relationship in

the

book, she wrote to Gillian to warn her. "Understandably, she didn't

reply

and I didn't expect her to. It wasn't an easy letter to write, but it

must

have been more difficult for her to read."

With

theatre, TV and film roles under his belt, Leonard tapped a new medium

in 1980: literature. His Devil's

Bedside Book - A Cynic's Survival Guide found him revisiting

Ambrose

Bierce's cynical definitions for everyday terms and phrases, and adding

quite a few maxims of his  own. It also contained a very

useful compendium

of Laws and Rules, such as Murphy's Law and The Peter Principle. This

was

followed in 1981 by his second book, The

Lowest Form Of Wit, a collection of some of the greatest sarcastic

put-downs from across the centuries, and from Leonard's own long and

varied

career. In 1981, he was busy filming Britannia

Hospital, a film which reflected British society of the time, where

most people were on strike, and the only funding for new projects came

from overseas. Leonard continued to return to the theatre as often as

possible,

and gave some dynamic performances in The

Rules Of The Game, Make

And Break, and Tartuffe.

1984 brought a new sitcom for Leonard - Tripper's

Day. He had turned down numerous scripts for pilots because they

were

merely "Perrin-cum-Rigsby clones", as he put it: "You have to avoid

playing

a carbon copy of someone you've done before - a very easy thing to do

if

you aren't careful." In an interview for TVTimes he said: "When I was

offered

Tripper, it was pointed out that it wasn't terribly deep stuff, just

smash-bang

basic comedy in short, sharp scenes. I said I wasn't averse to doing

anything

if I liked it", he added, "and this is fast and funny, and very well

written

by Brian Cooke." In the same interview he joked about the moustache he

wears while playing Norman Tripper. He grew it for his portrayal of King

John in a Shakespeare TV play, and kept it for Loot and the movie Water,

in which he starred with Michael Caine. He said: "Because of different

jobs overlapping I was forced to make the moustache become a fixture.

But

it definitely comes off at Christmas, and I'll be glad to see the back

of it." Sadly, Leonard never saw that Christmas. In October that year,

he played the role of Inspector Truscott in Joe Orton's Loot.

own. It also contained a very

useful compendium

of Laws and Rules, such as Murphy's Law and The Peter Principle. This

was

followed in 1981 by his second book, The

Lowest Form Of Wit, a collection of some of the greatest sarcastic

put-downs from across the centuries, and from Leonard's own long and

varied

career. In 1981, he was busy filming Britannia

Hospital, a film which reflected British society of the time, where

most people were on strike, and the only funding for new projects came

from overseas. Leonard continued to return to the theatre as often as

possible,

and gave some dynamic performances in The

Rules Of The Game, Make

And Break, and Tartuffe.

1984 brought a new sitcom for Leonard - Tripper's

Day. He had turned down numerous scripts for pilots because they

were

merely "Perrin-cum-Rigsby clones", as he put it: "You have to avoid

playing

a carbon copy of someone you've done before - a very easy thing to do

if

you aren't careful." In an interview for TVTimes he said: "When I was

offered

Tripper, it was pointed out that it wasn't terribly deep stuff, just

smash-bang

basic comedy in short, sharp scenes. I said I wasn't averse to doing

anything

if I liked it", he added, "and this is fast and funny, and very well

written

by Brian Cooke." In the same interview he joked about the moustache he

wears while playing Norman Tripper. He grew it for his portrayal of King

John in a Shakespeare TV play, and kept it for Loot and the movie Water,

in which he starred with Michael Caine. He said: "Because of different

jobs overlapping I was forced to make the moustache become a fixture.

But

it definitely comes off at Christmas, and I'll be glad to see the back

of it." Sadly, Leonard never saw that Christmas. In October that year,

he played the role of Inspector Truscott in Joe Orton's Loot. It was to be the final curtain for Leonard Rossiter. In his 1980 book

The

Devil's Bedside Book, Leonard had written "I love life and I don't look

forward to death at all." It came far sooner than anyone had expected,

least of all himself.

It was to be the final curtain for Leonard Rossiter. In his 1980 book

The

Devil's Bedside Book, Leonard had written "I love life and I don't look

forward to death at all." It came far sooner than anyone had expected,

least of all himself.

The play had opened at London's Ambassador Theatre in March to

favourable

reviews. Directed by Jonathan Lynn, it was the comic-horror tale of a

bank

robbery stash hidden in the robber's late mother's coffin, with the

body

disposed of elsewhere. Truscott, a corrupt police officer,

investigates,

and ends up sharing in the proceeds. In September, the production

transferred

to The Lyric Theatre, on Shaftesbury Avenue. It was here, on October

5th,

that Leonard suffered a massive heart attack and died. Very rarely ill,

he had been suffering some discomfort in his chest, but the doctors at

the Brompton Hospital who ran a number of tests found him to be

healthy,

and far fitter than other men of his age, 57. Leonard's co-star Neil

Pearson

remembers the events on that fateful Friday: "He'd come in, and

wandered

about in the wings before the show. He wasn't on first, but he always

did

that, just to get the 'feel of the house'. [That night, the house was

full,

and people were even standing at the back of the auditorium]. The show

started. We did the first scene. Leonard came on for the second scene,

off he went." A short while later, tannoy calls for Leonard were being

repeated, something which his fellow actors knew he never needed. They

all knew something was wrong. The actors on stage had run out of lines

and had started to improvise, after Leonard had missed his cue. David

John,

another actor in the play, rushed to Leonard's dressing room, but found

the door locked. The curtain was temporarily lowered on stage, and

Leonard's

door was forced open. He

was found sitting, slumped in an armchair. The call for a doctor went

out,

and heart massage was applied while everyone waited for the ambulance

to

arrive. By the time Gillian arrived at the theatre, Leonard had been

rushed

to the Middlesex Hospital, but he was already dead. The cause of his

death

was hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a congenital disease of the heart

muscles.

(See the special

page on Loot for a more detailed description of the events at the

theatre

that day).

There

are many words that describe Leonard Rossiter, professionally and

privately,

and many of them appear constantly throughout the tributes and

remembrances

on the pages of this web site. Professionally, he was committed,

concentrated,

meticulous, exacting, focused, driven, inventive, fastidious,

hilarious,

and above all: brilliant and unique. Personally, he was shy,

introspective,

competitive, ambitious, eccentric, witty, honest and generous. It is

easy

to say "There'll never be another..." about anybody whose talents are

sadly

missed, but in the case of Leonard no-one put so much energy and

concentration

into his roles, and got so much out of his audiences; or could play the

entire spectrum of human emotions with such believability; or be

respected

and revered by everyone he came into contact with, from the school

playing

field to his final performance; and yet remain an ordinary family man,

his fame never changing him. That is rare. There really was

no-one

like Leonard Rossiter.

Click

here to read a page of co-stars' personal, non-performance-related

tributes to Leonard Rossiter.

|

|

Text (c) Paul Fisher

Pictures (c) their

respective

owners.